Tim Bray’s post, Doing It Wrong is a great summary of the overall problem with large IT projects, contrasting the traditional practices of corporate IT with the more iterative, more realistic approaches used by Internet companies.

Having worked on dozens of projects over the years, this is a topic about which I have some thoughts.

Years ago it occurred to me that Amazon.com was a software company. That’s not news to anybody any more now that they’ve turned pieces of their infrastructure into cloud computing products that they lease out, but I realized it long before Amazon announced their Web services products, and even before they started outsourcing their online store and logistics to other retailers like Borders and Toys R Us. Early on, Amazon was thought of as a retailer, but their retail strategy was based on building the best software for running an online retailer. My guess is that Amazon.com knew from the beginning that they were in the software business, but a lot of companies that expend a large share of their resources building software don’t.

What I’ve also realized is that the best way to avoid failed software development projects is to avoid starting software development projects. Awhile back I worked with an organization that I won’t name. They were a very small shop that had a Web site, an online store, and an internal membership management application. All of them were custom and were maintained by an in house IT person who also performed every other IT task for this organization. The total head count at this organization was maybe five people, and yet they were maintaining complex applications built using ColdFusion and FileMaker. They had decided to rewrite these applications, combining them into a single application built using Ruby on Rails. The project was not successful.

While the scale was vastly different, the project was very similar to many massive IT projects. This organization’s entire business was run through this legacy software and the budget was very large by their standards. The rewrite was behind schedule, the requirements were not gathered well so the resulting application was not a good replacement for the (terrible) applications it replaced, and they were on the hook to keep Rails expertise in house or on retainer indefinitely because of this completely custom, highly specialized application they had built.

When I talked to them about fixing the new application, the question that popped into my mind was, “Do you guys even want to be in the software business?” Committing to this custom application meant that they would invest a sizable chunk of their resources into software development forever, and they lacked the expertise to manage such a project. The right solution for them really was to dump their custom application and use whatever existing software they could afford that would allow them to move forward, even if it was quite different from what they had before.

I think that’s true for a lot of organizations. The question people need to be asking is how little custom software can they get away with having. The ideal number is zero. If you’re working at one of those web design that rolls a new content management system for every customer, you’re doing your customers a disservice. Honestly, if you’re selling them your own proprietary CMS you’re probably doing them a disservice.

Software developers like to build things. And most developers are confident that they can provide something that perfectly solves whatever problem they’re confronted with as long as they can write it from scratch. Developers are horrible at estimating the long term costs of building applications yourself. And they have an incentive to be bad at it, because if they were good at it, nobody would let them loose to write custom software.

The first question everyone should ask when thinking about building custom software is, does building this give me a tangible strategic advantage over the competition? Specifically, does it provide enough of an advantage to make up for the amount you’ll spend on initial development and on maintenance and improvements going forward. Account for the fact that packaged software will likely be improving over time as well, so your custom solution may be great today, but the feature set in the packaged solution may blow away what you have two years down the road.

The second question is, how small can you start? The larger the project, the more likely it is to fail. And by small, I mean relative to the capabilities of your organization. If you have one in house developer who has other responsibilities as well, pretty much any project is large. You want to start with something you can release right away. Starting small is easier when you’re doing something totally new and difficult when you’re trying to replace something that already exists, but that’s really a warning against replacing things. Replacements for existing applications are the projects that are most likely to fail.

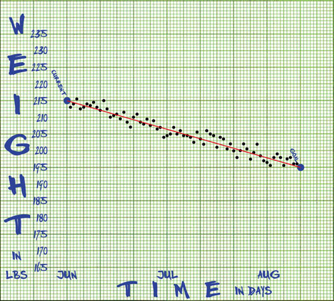

Back to the line diet. The graph here illustrates the entire concept. The Y-axis on the graph represents your weight, and the X-axis represents time. You plot your current weight at spot 0 on the X-axis, and plot your desired weight to the right on the date you hope to reach that weight, then you draw a line connecting them. Every morning when you wake up, you weigh yourself and plot your weight on the chart. If your weight is above the line, you “eat light” and if it’s below the line you eat whatever you want. I never drew a graph, instead I bought the iPhone application

Back to the line diet. The graph here illustrates the entire concept. The Y-axis on the graph represents your weight, and the X-axis represents time. You plot your current weight at spot 0 on the X-axis, and plot your desired weight to the right on the date you hope to reach that weight, then you draw a line connecting them. Every morning when you wake up, you weigh yourself and plot your weight on the chart. If your weight is above the line, you “eat light” and if it’s below the line you eat whatever you want. I never drew a graph, instead I bought the iPhone application

Is the iPad the harbinger of doom for personal computing?

In 2002, there was a lot of fear of Microsoft’s trusted computing platform, Palladium. The idea was that Microsoft was going to add new security to computers that was enforced in the hardware which would put an end to viruses and some other security problems but would also fundamentally change the relationship between computers and their users. Your computer would no longer be fully under your control, nor would it be functionally anonymous. Steven Levy’s original article hyping Palladium explains the purported benefits, then Ross Anderson explained what was scary about it.

In the end, Palladium was a total failure. It never went anywhere. But people at the time reacted very strongly when the traditional idea of the general purpose personal computer was threatened. People were afraid that if Palladium were implemented, the PC maker, application developers, and media companies would all be able to exert control over your experience.

Now we turn to Apple’s iPad. It’s just an iPod Touch with a big screen, but that’s all that many people need from a computer. You can use it to surf the Web, read email, listen to music, watch video, or compose documents. That’s the personal computer use case for many people. And I think a lot of people are going to buy them.

The fundamental difference between a Mac and an iPhone is that I can run any software I want on my Mac. I can buy it on a DVD, I can download it from the Internet, or I can compile it myself. I can get rid of OS X and install another operating system. The Mac is a general purpose computer in the classic sense. The iPhone is not.

Apple decides which software I can run on my iPhone. Apple provides the only means by which I can get it. The platform is for all intents and purposes, closed, and the hardware is closed as well. Sure, the iPhone is great to use, but the price of using it is that you’re rewarding Apple’s choice to bet on closed platforms.

What bothers me is that in terms of openness, the iPad is the same as the iPhone, but in terms of form factor, the iPad is essentially a general purpose computer. So it strikes me as a sort of Trojan horse that acculturates users to closed platforms as a viable alternative to open platforms, and not just when it comes to phones (which are closed pretty much across the board). The question we must ask ourselves as computer users is whether the tradeoff in freedom we make to enjoy Apple’s superior user experience is worth it.

The Setup just published an interview with free software pioneer Richard Stallman about the tools he uses. He uses a crappy Chinese netbook as his only computer:

If Apple is really successful, it’s likely that other companies will be more emboldened to forsake openness as well. The catch is that customers won’t accept the sudden closing of a previously open platform, that’s one of the reasons Palladium failed. But Apple has shown that users will accept most anything in an entirely new platform as long as it offers users the experience they want.

I think that it’s a real possibility that in 10 years, general purpose computers will be seen as being strictly for developers and hobbyists. The descendants of the iPhone and iPad and their competitors will rule the consumer market and people will embrace the closed nature of these platforms for the same reason that Steve Levy hyped Palladium almost 10 years ago — because what you get for trading off freedom is reduced risk. There will be few (if any) viruses, and applications will “just work.”

General purpose computing is too complicated for most people anyway, and the iPad’s descendants along with similar competing products from other companies will offer an enticing alternative. So I see the death of the traditional, open personal computer as a likely occurrence.

Will closed personal computing matter?

The other question that arises for me is whether, in the the long term, the computer you hold in your hand really matters. If all of the applications we use run on other people’s Web servers, and all of our data lives in the cloud, then the fact that our computers are closed appliances we use to get to the Web isn’t such a big deal.

When you look at the performance curve for JavaScript, it does not seem unreasonable to me to imagine that one day in the not too distant future there will be no difference in performance between desktop applications and applications running in the browser. Apple has done a lot to make it possible to build Web applications that are nearly indistinguishable from iPhone applications. It seems likely that every platform vendor will be following their lead, so for most users it won’t matter whether they launch an application by clicking on an icon or by choosing a bookmark in their browser. Indeed, on the iPhone you can already assign icons to Web sites as though they are full-fledged applications.

I foresee an era where people who really care about computing freedom use whatever closed personal computer is available, but run their open source applications on a virtual machine in the cloud somewhere running an open source operating system. Their data is stored in some other location, perhaps in encrypted format so that the fact that it’s not in their physical control matters less. It’s not quite the same as the traditional definition of a “personal computer” but it’s not any less free than what we have now, and it provides the benefit of being accessible from anywhere with an Internet connection.

A future where applications and data in the cloud are more our own than the computers on our desks seems bizarre, but I can see things playing out that way.

For more on the threat to open computing posed by the iPhone platform, check out this piece from Create Digital Music.