Like many people whose occupation and hobbies both involve sitting at a desk, I could stand to lose some weight. We’ve arrived at the time of year when a lot of people think that they could stand to lose some weight, too, and so I thought I’d talk about an approach to eating that has been working for me — the line diet. I read about the line diet this summer in a blog post at kottke.org. But before I talk about the line diet, I want to talk about weight loss in general.

There are hundreds of approaches to losing weight, but at the most basic level, they all work the same way. Losing weight requires you to consume less calories than your body uses. You can break it down mathematically. You have to deprive your body of 3,500 calories to lose one pound. If you eat 3,500 surplus calories, you’ll gain a pound. To lose a pound a week, you have to eat 500 fewer calories per day on average than your body is using. Diets are tools for managing your caloric consumption (making sure you’re eating the number of calories you intend to), managing your appetite, and in theory, managing your metabolism (encouraging your body to burn more calories than it would otherwise).

For starters, I’m not a believer in any diets that I’d classify as “metabolism hacks.” The most famous of these is the Atkins diet. I know a lot of people who have successfully lost weight that way, but most of them gain the weight back when they go back to eating a “normal” diet. In a more general sense, I’m not a fan of any diet that discourages you from eating normal meals consisting of fruits, vegetables, carbohydrates, and protein. I also find these sorts of diets aesthetically offensive.

Beyond that, I don’t have any opinion on diets. People should be on the diet that enables them to manage their food consumption and achieve their goals. If it works for you, do it. If it doesn’t, do something else. Some people eat one or two meals a day and feel fine, other people need to eat five meals a day to keep from going around hungry all the time. The world is full of people who want to tell you that one way works better than others, but everybody is different. The only thing that matters is whether the way you’re eating is helping you get to where you want to be. On that same note, if you’re not really committed to managing how much you eat, no diet is going to work for you. Just skip it until you’re ready to commit, you’ll be happier.

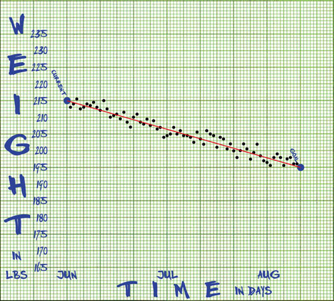

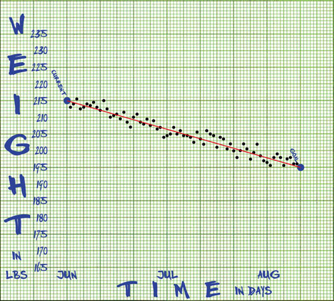

Back to the line diet. The graph here illustrates the entire concept. The Y-axis on the graph represents your weight, and the X-axis represents time. You plot your current weight at spot 0 on the X-axis, and plot your desired weight to the right on the date you hope to reach that weight, then you draw a line connecting them. Every morning when you wake up, you weigh yourself and plot your weight on the chart. If your weight is above the line, you “eat light” and if it’s below the line you eat whatever you want. I never drew a graph, instead I bought the iPhone application Bang Bang Diet, so every morning I just weigh myself and punch in my weight.

Back to the line diet. The graph here illustrates the entire concept. The Y-axis on the graph represents your weight, and the X-axis represents time. You plot your current weight at spot 0 on the X-axis, and plot your desired weight to the right on the date you hope to reach that weight, then you draw a line connecting them. Every morning when you wake up, you weigh yourself and plot your weight on the chart. If your weight is above the line, you “eat light” and if it’s below the line you eat whatever you want. I never drew a graph, instead I bought the iPhone application Bang Bang Diet, so every morning I just weigh myself and punch in my weight.

I’ve been using the application since August, and my goal was to lose about 20 pounds before January 1, 2010 — a little more than a pound a week. I am currently a bit below my end of year goal, so the project has been a success. The question is, why has it worked?

I knew I didn’t want to go on a diet that involved tracking or counting calories in any way. I know that works well for many people, but the accounting overhead just wasn’t something I was interested in. I also didn’t want to deal with dietary restrictions of any sort. Psychologically, that just doesn’t work for me.

The only thing you absolutely must do on the line diet is take “Eat Light” very seriously. If you really eat light, you will lose weight. The catch is that if you eat too much on “Eat Normal” days, you’ll see a lot of “Eat Light” days. It took me about a week to figure out that the best way to succeed is to eat less every day — my goal from the beginning has been to avoid “Eat Light” days entirely. That never worked out — I find that my line is pretty jagged, as soon as I hit a new low, I tend to gain two to four pounds, and sometimes that puts me over the line and I have to eat light. I almost never eat as much on any given day as I ate almost every day before I started the line diet.

I mentioned above that diets serve two functions (metabolic hacks aside) — managing caloric intake and managing appetite. The line diet only takes on the first, managing caloric intake. As far as managing appetite goes, I just got used to being hungry more than I was used to. The most powerful feature of the line diet for me is that you’re accountable to the scale (and to yourself) every morning. It’s a powerful incentive not to go for seconds or to snack thoughtlessly. I also try to eat the minimum possible to kill my appetite. One of my neighbors is this incredibly skinny Italian lady. She came over once and saw we had some candy she really likes. She took one 30 calorie piece (I looked it up). I learned something from that.

I still have no idea how many calories I eat every day (although it wouldn’t be hard to figure out), and I didn’t start thinking about how many calories are in a pound or how many calories I wasn’t eating until Thanksgiving, when I read in an article that there are 3,500 calories per pound. I just became a lot more deliberate about what I ate.

I have no idea if the line diet will work for you, but I’m very pleased at how well it’s worked for me. Good luck in keeping up with your New Years’ resolutions.

Update: One tool I’ve found essential in following the line diet is a really nice bathroom scale. I have a Soehnle scale that is very accurate and weighs to a tenth of a pound.

Update (January 5, 2011): Here’s a link to my “one year later” post.

Back to the line diet. The graph here illustrates the entire concept. The Y-axis on the graph represents your weight, and the X-axis represents time. You plot your current weight at spot 0 on the X-axis, and plot your desired weight to the right on the date you hope to reach that weight, then you draw a line connecting them. Every morning when you wake up, you weigh yourself and plot your weight on the chart. If your weight is above the line, you “eat light” and if it’s below the line you eat whatever you want. I never drew a graph, instead I bought the iPhone application

Back to the line diet. The graph here illustrates the entire concept. The Y-axis on the graph represents your weight, and the X-axis represents time. You plot your current weight at spot 0 on the X-axis, and plot your desired weight to the right on the date you hope to reach that weight, then you draw a line connecting them. Every morning when you wake up, you weigh yourself and plot your weight on the chart. If your weight is above the line, you “eat light” and if it’s below the line you eat whatever you want. I never drew a graph, instead I bought the iPhone application

The advantages of mass production

The August 13 issue of The New Yorker had an article by Atul Gawande (one of my favorite writers) about how hospital chains are increasing quality and lowering costs by taking the individuality out of the practice of medicine. In it, he compares the way hospitals treat patients to the way Cheesecake Factory treats customers. It’s a great article, and the lessons in it apply to more than just the medical industry.

I particularly liked this description of the value proposition of chain restaurants:

There’s an important point to be made, which is that the idea of manufacturing is to produce things at a predictable cost and at a predictable quality level. In some case, that means flimsy T-shirts that you can buy for two bucks, in others it’s a Mercedes Benz car that costs many tens of thousands of dollars. In most cases, the best handmade items incorporate no small amount of individual brilliance and have many advantages over manufactured alternatives. At the same time, there are lots of handmade items that are just terrible. If you haven’t invested the time or effort to choose between them, the predictability of the manufactured option is often a safer bet.

I think about this a lot when it comes to restaurants like Chipotle. Is Chipotle as good as the better California-style burrito restaurants? Of course not. But most towns don’t even have a non-chain burrito place, and even in those that do, there are plenty that aren’t as good as Chipotle. Your best bet is to do research ahead of time and find a truly outstanding dining experience. But barring that, trusting in the luck of the draw can often turn out to be a poorer choice than going with a known quantity like Chipotle.

Gawande’s argument is that the discipline imposed by chains may make even more sense in the medical field than it does in restaurants. Certainly it’s the case that for the person who wants to find excellent food to eat, the resources to help out are nearly limitless. Not so for the person seeking excellent medical care. Having the option to choose a hospital with predictable, high quality results would represent an upgrade for nearly every patient.